Donating to medical research? Here's why you shouldn't donate to cancer research

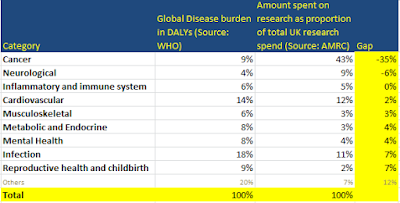

If you're going to donate to medical research, don't donate to cancer -- there are better choices. Cancer accounts for 43% of the research spend, but only 9% of the disease burden, and you can see in the chart below that it's an outlier.

Having said this, it may still be a better choice than some other (non-medical-research) charities.

This chart seems to lead to the conclusion that you should pick other areas of research to fund, rather than cancer, on the grounds that it's already a crowded funding area. Better areas appear to be reproductive health & childbirth and infectious disease. If you want to see a table of the data from this chart, together with the figures that show the gap between the disease burden and the research spend (this gap being proportional to the distance of the point from the red line on the above chart) check out the footnote1.

Reasons why you might disagree with this conclusion

1. Tractability - scale and neglectedness aren't the only things that matter

2. You may disagree with the DALY weights

3. The research spend figures are only showing part of the picture

4. Some categories may be being researched, but aren't captured in these stats properly

5. This chart uses global disease burden -- you may care about the local disease burden

6. These categories are too crude

1. Tractability - scale and neglectedness aren't the only things that matter

The chart above may seem to suggest that the scale of the problem is the only factor to consider. This is not the case. We may choose to fund something because we think that more progress will be made if we fund that area; in this scenario, we may say that this is a more tractable (or "easy") area of research. In general tractability is good, because funding something with a higher chance of success is better than funding something with a lower chance of success, all other things being equal.

However, we know that the funds *aren't* being allocated to cancer as opposed to other areas because donors have taken this into account and consider cancer to be more tractable.

So should we expect better tractability, or better progress, from well-researched areas (such as cancer) or less-well-researched areas (such as mental health)?

- Cancer: Cancer Research UK talk about the current cancer survival rate having reached 50%, and their aim to reach 75% by 2034; my reading of their language is that they are optimistic that cancer (an area which already has a track record of progress) is a good tractable area to fund.

- Mental Health: MQ (a mental health research research charity) seem to consider funding under-funded research to be an opportunity; as far as I can tell, they have made no explicit claims that (for example) mental health may have lower hanging research fruit, so to speak. However implicit in their language is the belief that tractability for mental health is at least as good as that of cancer.

My -- admittedly cursory -- conversations with researchers suggest that there are arguments both ways as the above examples suggest. Sometimes an under-explored area can yield low-hanging fruits; sometimes an area being under-explored means that researchers haven't quite worked out the best research questions to ask yet, which might mean that research in that area is leading nowhere.

To my mind, both arguments seem reasonable, so I'm inclined to assume that we can treat tractability as roughly equal across health categories. If anyone can give a better, and evidence-based, indication of how to treat this, I would love to take this into account.

2. You may disagree with the DALY weights

Determining the disease burden involves using a measure commonly used by the WHO called the DALY, which counts how many years have been lost from people dying together with the number of years spent in disability. DALYs generally assume that being disabled is better than being dead, but how much better depends on the disability; a weighting factor is assigned to each type of disability2. However getting these right is hard, and you may disagree with the WHO on this.

3. The research spend figures are only showing part of the picture

It's true that the figures focus just on UK spend, and also ignore government expenditure. It could be that, for example, that UK charitable cancer research spend is really high to make up for a lack of government spend on cancer research, or a lack of spend by other developed nations. I suspect that this isn't true, however I haven't done the digging to check.

The reason I suspect that this isn't true is (to echo an earlier comment): we know that the funds *aren't* being allocated to cancer as opposed to other areas because donors have taken this into account and are making up for a lack of government or international research spend.

4. Some categories may be being researched, but aren't captured in these stats properly

For example, 2.7% of the global morbidity burden comes from road injuries. It could be that research is happening on road injuries, but (perhaps) it's not captured in the statistics because the source of the data (the Association of Medical Research Charities, or AMRC) used data that didn't treat this as medical research.

Overall, I don't think this is likely to be a concern, except in "Other", which in any case is a fairly unhelpful category.

5. This chart uses global disease burden -- you may care about the local disease burden

Interestingly, I had assumed that changing the global disease burden to the UK-specific disease burden would account for the apparent over-allocation to cancer, however it appears that this only goes part of the way towards doing this -- there is still a material over-allocation to cancer based on the UK prevalence of cancer. I've created a copy of the above chart, but replaced the global disease burden with the UK-specific disease burden -- you can find the chart below3.

6. These categories are too crude

To a certain extent, this is a fair criticism -- for example, lumping together several different metabolic and endocrine diseases leaves open some of the uncertainties that arise from lumping things together; e.g. maybe the proportion spent on diabetes research is (perhaps) higher than the proportion of disability burden attributable to diabetes, but we aren't seeing it because the disease burden for non-diabetes conditions within the metabolic/endocrine category is also quite high. (I haven't checked whether this is the case.) As a later piece of work, I may see whether it's possible break those categories down further.

In particular, "Other" is a notably crude and unhelpful category; it is likely that it includes some sub-categories which are more neglected than reproductive health or infectious disease, so seeing this breakdown could be useful.

However I don't think it detracts from the conclusion about cancer -- it's still true that the UK allocates 43% of its research funding to cancer, whereas the only 9% of the global disability burden is for cancer.

A minor note...

In case you're feeling like you've seen something like this before... after the ice bucket challenge there was an infographic doing the rounds that compared how much money research charities got with how much they kill people. I would suggest that this chart is in fact much better than that infographic -- if you would like to know more, I've expanded on this in a footnote.4

And lastly, apologies to international readers for the UK focus of this piece. I suspect that its conclusions would still apply in most other countries in the developed world, but have not checked this.

APPENDICES & FOOTNOTES

How this was calculated (data sources):

- Source of the data about disability burden: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ which (I believe) ultimately comes from the WHO. A bit of further useful info on understanding the health categories came from here: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/Projects/GBD/GBDcause_list.pdf.

- Source of the data about research spend: http://www.amrc.org.uk/blog/comparing-charitable-and-government-funding-across-the-medical-research-landscape which is a blog post by the AMRC, or Association of Medical Research Charities. The ultimate source is the UKCRC: http://www.hrcsonline.net/pages/data

Nuance 1: generic health relevance

The source data about the charity research spend included a category called "generic health relevance". I thought this to be an unhelpful category for this analysis so I excluded it. (i.e. I recalculated the figures accordingly, so the original figure for cancer research was 37.7% of the total and generic health relevance was 13%, so I took the 37.7% as a proportion of the remaining 87% of the spend (excluding generic) which is how I got to 43%)

Nuance 2: marrying up different categorisations

The process involved taking data from two different data sources, which involves marrying them up. The marrying up process took some time - it involved going through a fairly lengthy list of quite specific health conditions, finding out what they were if necessary, and then checking which category they belonged to. The only example that I could find that seemed to fit very squarely into more than one category was inflammatory bowel disease, which clearly could be argued to belong in the "Inflammatory and Immune System" category, but which I put into the "Metabolic and Endocrine" category. This item constituted 0.15% of the total disease burden.

The full spreadsheet with all the calcs can be found here (assuming that you have MS Excel, you may want to download the document once you've followed the link, and then view the document in Excel).

1 Below you can find the data underlying the chart. The column in yellow on the right hand side shows the difference between the two numbers, so cancer has a large negative number because it gets lots of funding compared to its disease burden; infectious disease and reproductive health & childbirth have the largest positive number (excluding "other"), which suggests that they are the most underfunded.↩

2 Source: table 3.1 on page 30 of this chapter about the Global Burden of Disease concept on the WHO website. This table shows just a few examples of disability weights (it's not the comprehensive list)

↩

3 This is a copy of the chart comparing global disease burden with UK research spend, but I've replaced global disease burden with UK-specific disease burden↩

4 Below is the infographic referred to earlier which was doing the rounds after the ice bucket challenge back in about 2015.

↩

|

| Source: Vox |

There were several reasons why this infographic was less than ideal

- it counted number of deaths, but gave no credit to diseases that make us suffer, but don't kill us much

- it used a poor metric of how much charitable funding went to a cause area, by simply picking an individual charity and indicating how much money that charity received, rather than aggregating across all the charities that fundraise for that area of health research

- this post includes some valid criticisms of it from an infographic design perspective

(Note the version shown here is quite small -- scroll down for a larger version if you're interested)

Larger version of the infographic from Vox shown above: